Fidelity Reminds ETF Industry It Doesn't Have To Care

Why Pay-to-Play won't ever go away.

News Flash: People Like Free.

Free is a good price.

It’s how we got Fortnite, and Radio, and a terrible internet. People hate paying for things.

That’s what Fidelity was counting on when some beancounter in their custody division decided to make a stink about 9 ETF issuers (most of whom nobody outside the industry has ever heard of) not signing their revenue sharing deal. And they’ll win. They always win.

The Headline

If you missed the story, it’s very simple:

Before 2019, in general, if you wanted to buy or sell an ETF (either as a rando or as an advisor) you paid some commission. At Schwab, it was $4.95, or more for large trades.

In Jan 2019, Fidelity kicked off the “no-commission-ETF” thing announcing a deal with Blackrock.

By the Pandemic, we had Robinhood and E-Toro and everyone other than Interactive Brokers all racing to zero as fast as possible.

Fido makes this announcement, and FinTwit looses its collective mind, and a handful of stories get written about it in the usual places (BB, FT, industry sites.)

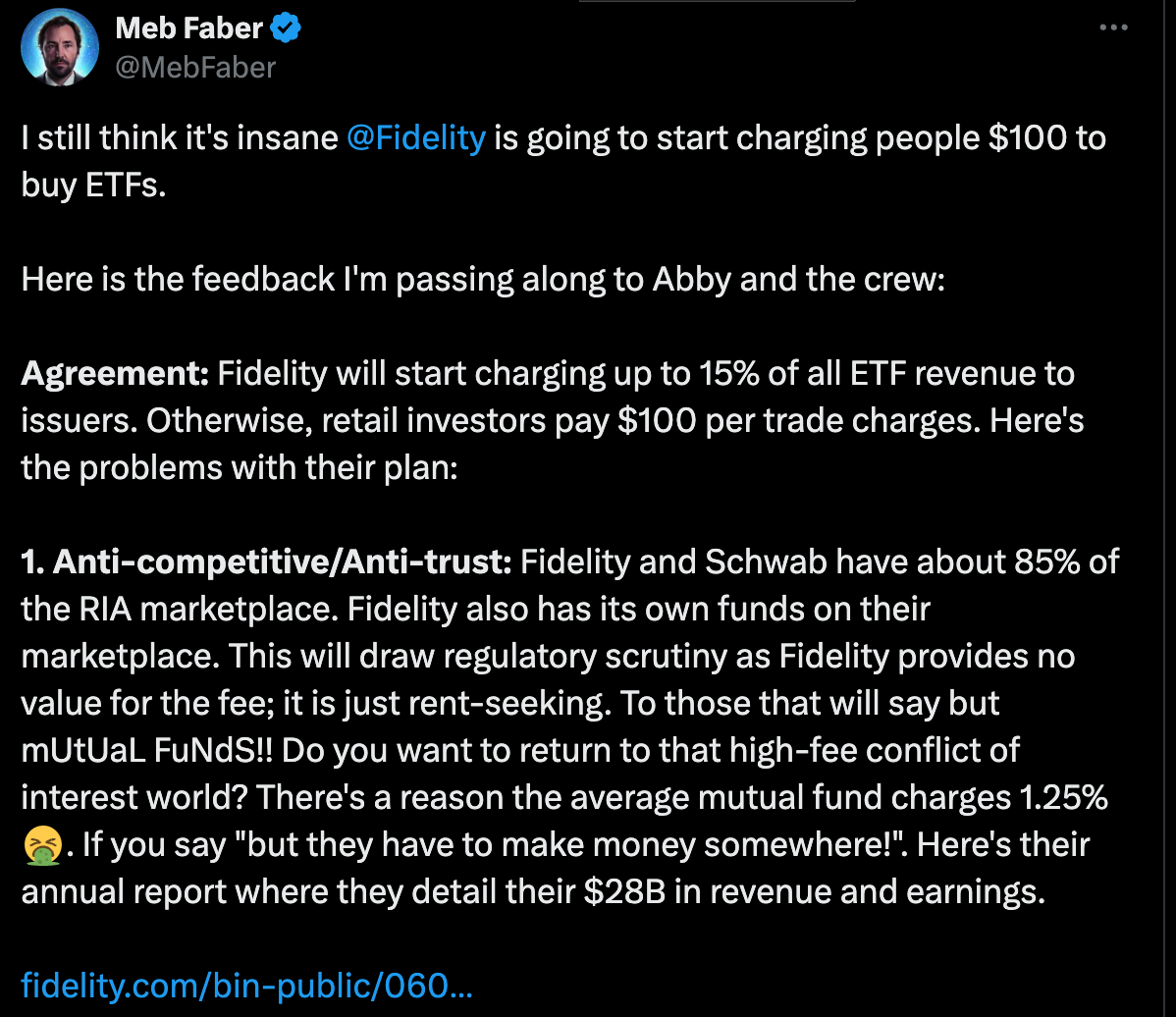

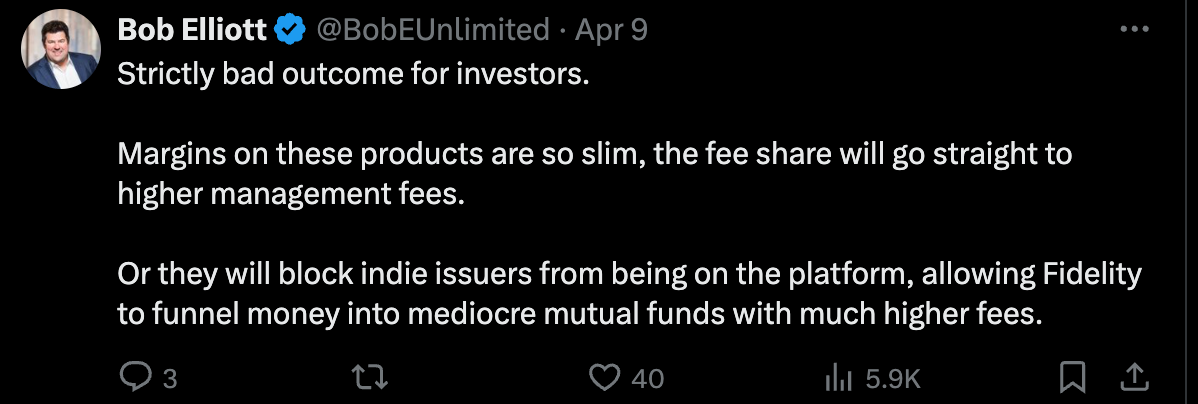

A good summary tweet comes from my friend Meb Faber at Cambria:

With lots of comments that echo Bob Elliot here:

To which my response is:

Companies are Not Your Friends

The weird irony of the ETF, Financial Advice and Retail Investing market is that its dominated by three companies with RADICALLY different ownership structures and approaches to transparency.

On the one hand, we have Fidelity, which is completely privately owned. It’s a family business, the same way Cargill is. While various corners of their business are regulated and thus have to produce minimal documentation, they can do essentially whatever they like within the bounds of legality.

All the way at the other extreme is Vanguard, the world’s only Mutually-owned pure asset manager (and broker, and advisor, and marketing agent, etc…) While “owned by the funds” it actually makes it less transparent than you might think. Teasing out something like “exactly how much did Vanguard spend on TV ads last year?” or “how does executive compensation get handled” isn’t precisely impossible, but it’s hardly simple. Their approach has generally been to tell folks what they think they should know … so for example, they still don’t publish actual daily holdings on their ETFs, because they’re share classes of the mutual funds, and Bogle always wanted to discourage trading or some other excuse.

In the middle is Schwab, a pretty straightforward public company I have been tracking for decades, that produces more-than-required levels of transparency not just on their businesses, but on their clients.

And these three companies have very different motives:

Vanguard: Plow any money made back into making the funds bigger (cheaper) and better.

Schwab: Make money for shareholders the way most public companies do: generate bottom line profits (the business), and increase multiples (the brand and growth story).

Fidelity: Secure the Bag for Abby Johnson and other private shareholders.

Of the three, only Schwab really gives a hoot about what anyone “thinks” about their business, beyond the obvious “you need to retain employees, avoid regulators and not get sued” level of good behavior every going concern needs. Of the three, only Vanguard even has a claim to being on “investors’ side” and they usually get bitched at for being too nanny-like in what they allow on their platform.

Why They Don’t Care

Let’s get some numbers on the board. This is the entirety of the publicly available information that includes numbers from Fidelity’s PPT they call an “Annual Report:”

But lest we forget …

To put this in a bit of perspective, Schwab’s 2023 was nowhere near this good — just under $19 Billion in total revenue vs Fido’s $28 Billion here. Of course, Fidelity is still predominately an asset manager first and a custodian and bottle washer second — that’s the $4.9 Trillion in Discretionary assets up there (compared to under about $1 Trillion for Schwab).

The good comparison is in that vague “Assets Under Administration” bucket — a slop bucket which likely includes all custodied assets from my mom’s cash line in her IRA to their largest custody-only client — Fido has $12.6 to Schwab’s roughly $9 Trillion.

The number I’ve always looked at for distribution is “take rate” — how much does a firm get paid to be in between the individual and the asset. I’ve been tracking it on and off for decades, and here’s Schwab’s the last three years:

2023: 0.267%

2022: 0.294%

2021: 0.228%

That’s revenue across all client assets, divided by the AUA. For my entire career, the mid 20s has been very sticky for Schwab, and they’ve generally been cheaper than anyone else (don’t even think about running it on a regional B/D like EdJones, it’ll make you blush.)

The business mix shifts: from commissions to asset management to revenue shares to (especially) spread income, but the baseline doesn’t shift much. And Fidelity’s take rate? Based on the unverifiable numbers they published, is currently about 22 basis points ($28.2 billion / $12.6 trillion).

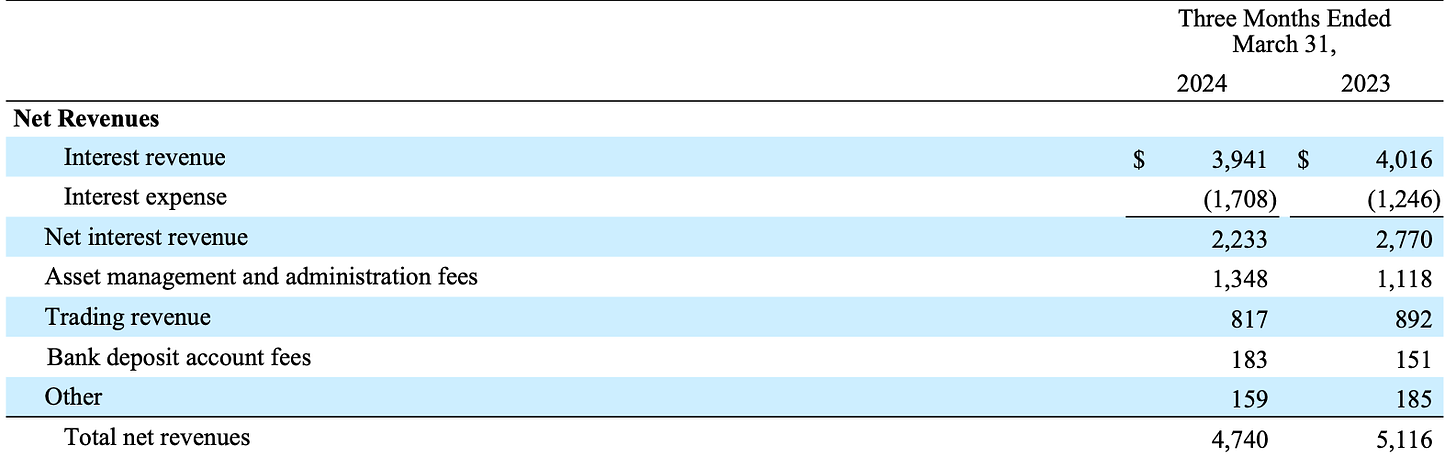

Its not that these numbers NEVER move — in 2000, when Schwab crossed $1T in assets for the first time, revenues ballooned to the ungodly amount of about 45 basis points, but the mid 20’s seem very, very sticky. Part of the reason is that the *only* thing that really matters in brokerage anymore is net interest income: Here’s Schwab’s latest quarter for instance:

We don’t have nice tables like this for Fidelity or Vanguard’s brokerage business, but let me assure you, if your job is managing for revenue at any of these firms, the only thing that really matters is getting cash balances from customers into the system so you can shellac anyone dumb enough to leave their cash uninvested.

Everything else, as interesting or profitable as it might be, is a distraction. That’s why all of these firms are always marketing the hot-dot to customers: you want digital assets? A physical advisor? A robo-advisor? A CD? A bank? You name it, they’ll make it and offer it to you “for free” so you deposit some cash and forget about it.

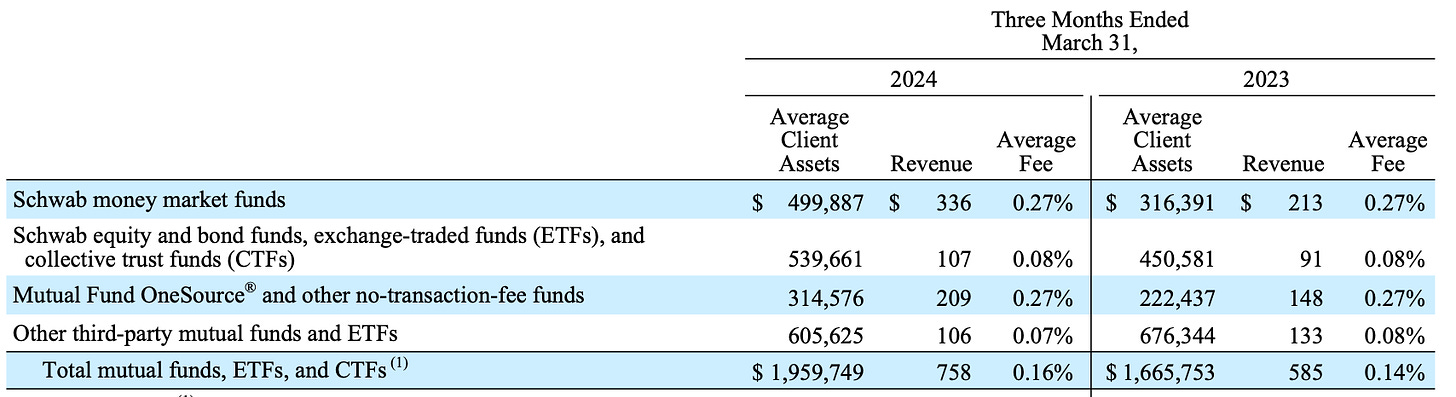

Of course, like any store, they have to stock the shelves with something: their own products, and competitors, which of course they charge fees on:

Again, I’m picking on Schwab, but I should point out I’ve been a customer since the elate 1980s, and partly *because* they’ve always set the bar for transparency on this stuff. Note that “One-Source and other NTF Funds?” line? — 27 basis points on average.

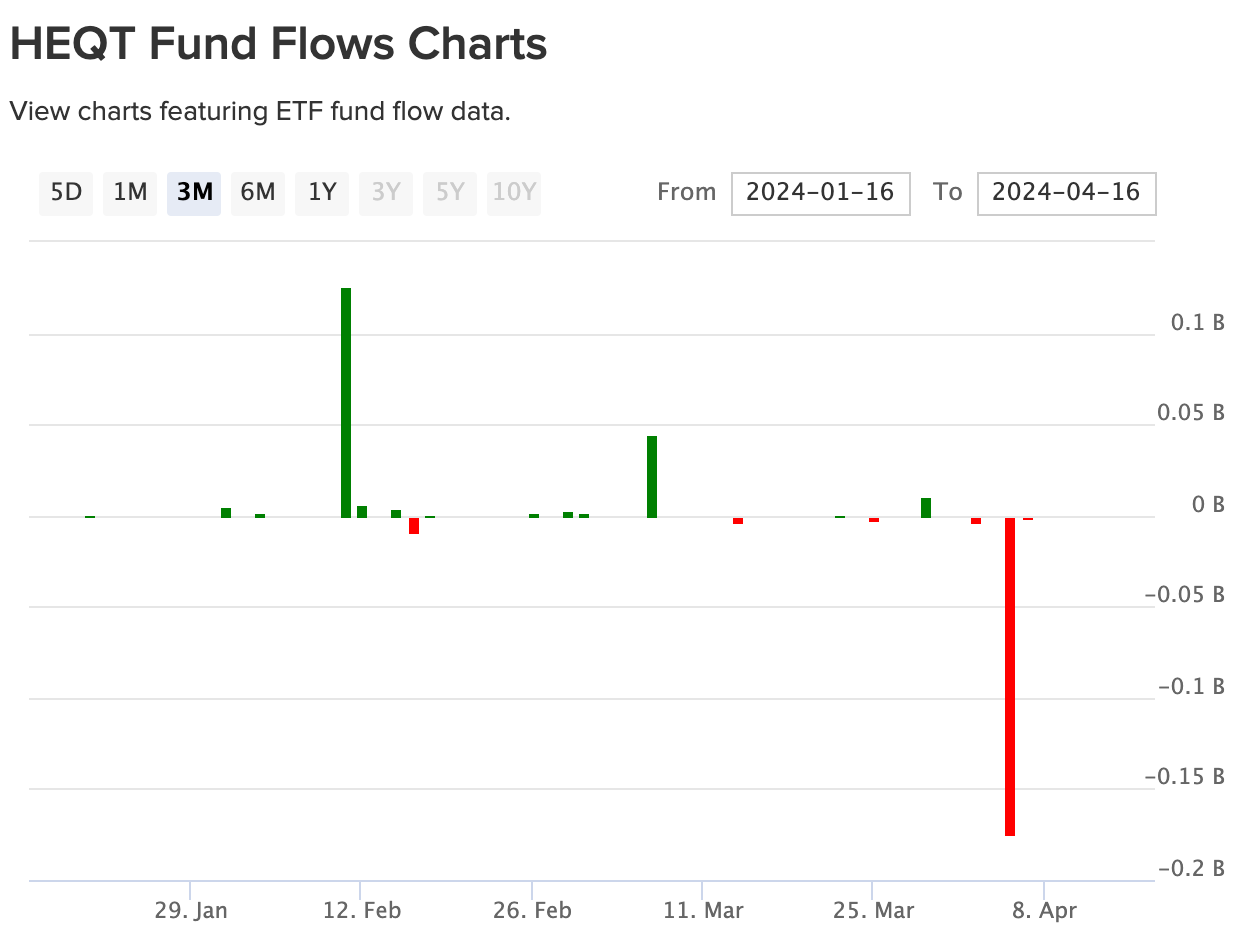

Schwab may have been a nicer negotiator, but they’re still playing the pay to play game. The egregious move by Fido was putting out a public press release that caused funds to get puked out of models (I feel for Simplify here):

As Meb Faber put it in his tweetstorm:

I concur. This is in fact a dick move. But that’s what it is: a dick move by a private company who owns a giant supermarket you’d like to have shelf space in. And no matter how much you enjoyed the free-look, someone, somewhere, is going to end up paying for that shelf space.

What Happens Next?

I’ve had a *lot* of discussions on this topic in the last few weeks. Here’s a bunch of things people are talking about that won’t happen, and one that will:

The (Insert Regulator) Should DO SOMETHING! This isn’t going to happen. The jurisdiction here is firmly with FINRA (if someone thinks the SEC has a hand in broker-dealer sales practices, I’d love to see the links). FINRA basically never gets involved in these kinds of disputes (they’re paid by their members after all).

It’s Anti-Competitive! The FTC should get involved! While it is in fact anticompetitive for the ETF industry, I think it’s a tough case to say that a firm can’t preferentially treat different suppliers. You can’t buy lots of things at Vanguard. Private companies aren’t under some legal obligation to treat every business transaction equally, as long as they aren’t, say, discriminating based on a protected status. However, it’s still super gross and feels like Fido “punching down” on the little guy. But this is America. There are lots of things and people that are super gross that aren’t illegal.

Advisors/Investors will Leave! No, they won’t. The (non-dollar) switching costs are enormous in financial intermediation. Will it nudge an incremental new advisor to just lean into Altruist or Interactive Brokers a bit? Maybe at the edges. Will it move a number you will ever see inside the rounded-decimal places of any report you’ll ever read from Fidelity? Never.

Fidelity is Risking it’s Reputation! Maybe, but who cares. What are you going to do, short their stock? Start a boycot? Picket? Seriously? You might care. They have no reason to.

…and finally…

Everyone will Roll Over and then Costs will Go up! Investors will pay! Yup. Sorry, but this is precisely what’s going to happen. Quietly, most other distribution avenues are already or will soon be taking their pound of flesh, and yes, in the end, investors will pay. How could it be otherwise? We are, after all, the end-consumer!

Same as it Ever Was

I’m not defending the move by Fidelity here — at best it’s ham-handed and wildly too much, too fast, without context. At worst it’s just plain stupid and won’t make them any more money. But I also do not believe that the last 20bps or so for distribution in financial services is every going to really go to zero. (Nor do I think we revert to opening individual accounts with each fund manager to avoid this — which was how it worked in the ‘80s.)

Free is always a fake price. Free means someone else is paying, or you’re paying and just haven’t figured out how. “Free Shipping” is never free.

If you are a large asset manager with a well known brand — Blackrock, PIMCO — you have massive entrenched advantages that are not illegal. You can bully your way onto platforms, you can spread your costs over broader pools, you get more bang for your marketing dollar, and your margins are better. It has been this way since the 1940s.

If you are a small asset manager who is relatively unknown — most of the ETF industry under the top 15 or so firms — well, you’ve got it much harder. You’re going to have to spend much much more for marketing and distribution. You’re going to have to do a lot more hand-to-hand combat. You’re going to need to be either very lucky, or very good. It has been this way for most of my career.

This isn’t new and it’s not illegal. It’s the core of western-style winner-take-all capitalism. I may not like it. You may not like it. And yet, here we are.

{Backedit: I mistakenly wrote “Abby Joseph Cohen” for “Abby Johnson” when dictating this and failed to catch it whilst in a rush today. Apologies.}