Why the Active/Passive Debate Matters

We're smart. We can hold two ideas in mind at once.

Oh look another twitter fight about passive investing.

Every few months, an academic does a piece of work on passive investing, and sides get picked before anyone does any reading. In this case, Acerbic Iconoclast Mike Green posted this:

(Substack isn’t letting Youtube in today, but here’s the link to the paper being presented. It’s a good and nerdy 15 minutes on how passive block trades clear and the impact of share issuance and buybacks.)

But the research in question never even got discussed, because it immediately ran into the wall I spent most of my career building — the core case for passive investing.

That’s legendary advisor Rick Ferri - someone I consider smart, wise and good -shutting down any attempt at conversation.

And this is when I get frustrated.

Let me say for the first of several times: passive investing works. And thus it is, I suppose, reasonable to ask “OK, but if buying cheap-beta is the best answer for the vast majority of individual investors, why should we care if Passive causes problems?”

Rick’s right — if you, constant reader — are solely concerned with selecting the best pool of investments right now, never to think on it again, you shouldn’t be reading this blog, or anyone’s FinTwit feed, or watch CNBC, or read the Wall St. Journal.

But while passive investing works, it also perturbs the markets being invested in, and that’s worth exploring. I have no idea how to be intentionally incurious about this. It’s a bit like saying “look, DDT kills mosquitos and has clearly saved lives lost to Malaria… who cares if it causes birth defects? At least you’re alive!”

I think we should care, and be curious, and support the academics chasing the issues around passive investing, because as far as I know, nobody has ever done much good through willful ignorance.

So what’s a real concern, and what’s a “concern” about passive? Strap in.

“Indexing is Killing Price Discovery!”

The longest running panic about passive investing is that it blows up public-market capitalism. One critical argument against passive came back in 2016, when Alliance Bernstein published the now classic “The Silent Road to Serfdom: Why Passive Investing is Worse than Marxism” by Inigo Fraser-Jenkins et al., in which they make a reasonably compelling case that a predominately passive market is a bad way to decide where a capitalist society allocates new capital, concluding:

While we recognize that the active vs passive investing debate is nowhere near any policymakers to-do list, we suggest that when decisions on fiduciary responsibility, stewardship, market structure and management of public pension assets are taken that at least the broader benefits to society from active allocation of capital are taken into account.

which was rebutted by Burton Malkiel in the Journal.

“In a free market system, we can expect that advantageous arbitrage opportunities are exploited by profit seeking market participants no matter how many investors index…. To be sure, index investors are free-riders… But free riding on price signals provided by others is hardly a flaw of the capitalist system; it is an essential feature of the system.”

The thing is, they’re both right. Active managers are needed to take risks and make big calls about where Billions in capital should be spent. The problem with modern markets is that a lot of the big decisions about capital allocation now happen either out-of-market (through VCs and Private Equity), or happening inside mega-cap companies like Microsoft and Apple through M&A and moon-shot projects.

But here we have the core problem: the Bernstein paper is talking about flows, and Malkiel is talking about holdings. Malkiel is basically saying indexing can’t “bid up” anything because there are no choices, but his core premise is a bit of a giant “if” — he says himself:

“Indexing does not involve simply buying an index of large companies, such as the S&P 500… In principle the index investor should buy all the stocks available in the market to achieve the performance of the entire stock market.”

This would be great, if anyone bought single-ticker, all-asset total market funds, but we live in the real world. Just in ETFs, over $1.5 Trillion tracks the S&P 500 specifically, with another $1 Trillion basically doing the same thing in near-identical indexes. The entire category of “Total Market” ETFs sits around 1/5 of that. Essentially “nobody” actually buys the entire market and then never trades.

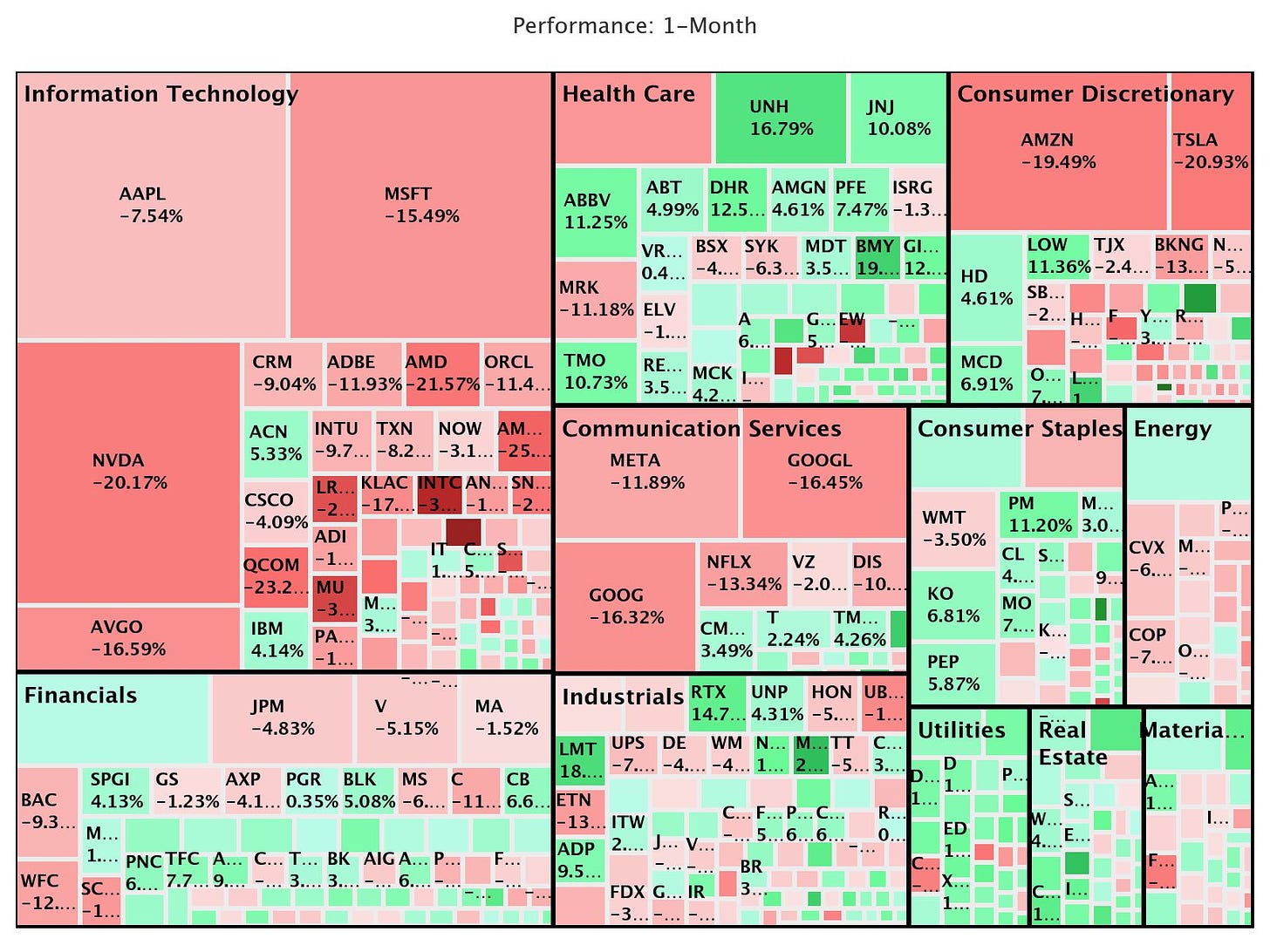

But mostly, I cede this point. If what we’re worried about is the market “not noticing” when some company cures cancer because “everyone” is just buying SPY, that’s a silly argument. Just look at the last few weeks in the S&P 500:

Sure, the Mag7 is down a lot, but its not like they “dragged” JNJ down, which has 30% on NVDA in the last month. So price discovery is obviously happening.

But if you’re talking about the much less market oriented “allocation of societal capital,” well, ol’ Fraser-Jenkins probably has a point. We don’t use public markets to allocate societal capital through IPOs like it said in my MBA textbooks.

“If everyone sells Active to buy Passive, everyone still just holds the market!”

This is the argument made by Avantis in their recent rebuttal to there being anything to see here:

The theory is clear that passive market holders shouldn’t have any significant effect on relative stock prices. It’s the non-market holders, including asset class investors (index or active) and, in particular, growth-oriented investors, who are more likely to push prices.

Which would be fine if the primary source of ETF and Index Mutual fund flow every day was just more people selling Fidelity Magellan to buy SPY, but it’s not: it’s new money. Just target date mutual funds/CITs tracked by Morningstar pull in about 150B a year, and my back of the envelope math on contribution rates, participation rates, and equity allocations from EBRI gets me to an annual new-money contribution of about $500Billion just into equity, just from U.S. retirement savers. That’s before any money comes “off the sidelines” and buys a single ETF share. It’s before anyone sticks a fund in their IRA. Half a T, year after year, going into a $45T market? Come on, of course it has SOME impact.

So to me, it feels like slightly disingenuous hair splitting to say “the passive market holder” shouldn’t have any price impact. All holders have zero price impact. That’s what holding means — you neither-take-nor-offer any information about pricing. Prices are only set in transactions (unless your a PE accountant), and in modern equity markets, transactions are mostly flow rather than reallocation within the market. Money coming from outside equities, to go into indexes.

Flow-impact is where all the cool research is being done, led by Gabaix and Koijen’s Inelastic Markets Hypothesis and expanded on in Bouchard’s Microstructure follow-on. If they’re directionally right, that $.5 T means about $2.5T in impact, or something like 5%. My napkin math is likely off by percents in some direction, so call it anywhere from 3-7%. That’s the potential tailwind which Bouchard comments on:

If order flow is the dominant cause of price changes, “information” is chiefly about correctly anticipating the behaviour of others, as Keynes envisioned long ago, and not about fundamental value. The notion of information should then be replaced by the notion of correlation with future returns, induced by future flows.

For example, when all market participants interpret a positive piece of news as negative and sell accordingly, the correct move for an arbitrageur is to interpret the news as negative, even if doing so does not make economic sense. Of course, if all market participants are rational and make trading decisions based on their best guess of the fundamental value, order flow will just reflect deviations from fundamentals and the efficient market picture is recovered.

Honestly, this idea that flows are much more important than fundamentals seems to trigger a lot of people. But I have yet to read much of a counterfactual on it. Looking at the sell off in the past week, it’s hard to argue “everyone” thinks NVDA is just 20% fundamentally less important than it was a week ago. Of course there are folks speculating on single names. But a lot of folks also just hit the sell button on their indexed (ETF/Futures Position/Options Trade/Swap/Mutual Fund/CIT), and NVDA was a monster holding.

Obviously lots of things influence stock prices. Obviously it’s messy. But wading into the mess and figuring out things like how different kinds of stocks respond to different kinds of flows is interesting and important work (thank you Valentin Haddad!), and we should support it, even if it’s uncomfortable.

Embracing Paradox

One symptom of being a hyper-rational left-brain-locked human (hand up), is an inability to handle paradox — that two things seemingly in conflict can both be true. Well, here’s a layer-cake of modern market paradox:

1: The very best individual strategy to increase portfolio value is, on average, to buy the entire market at the lowest possible cost.

2: The more investors take that advice, the more they “bid up” the value of the market *as a whole* just through flow.

3: Block flows — specifically block trading in index products which encompass a vast, multi-product, derivative laden set of underlyings — has a larger impact on market values than seems “intuitive” — with impact ranges of >5X pretty well established (to my discernment, but hey you be you) in the literature.

4: No, big Indexers and Index Managers are not colluding in back rooms to make individual companies less competitive. (I find the academic work here deeply uncompelling.)

5: Yes, there are real corporate governance concerns about a handful of large companies having the proxy on a giant swath of global businesses. (Although 90% of the media coverage makes this sound nefarious when it’s largely just practical and technical issues).

In other words: Passive has and continues to have both salutary and deleterious impacts on the state of things. And yes, something that is good for the individual can be bad for the whole. That’s the literal definition of the “tragedy of the commons.”

“Men pay most attention to what is their own: they care less for what is common."

- Aristotle.

“The Boomer Selloff will Tank Markets!”

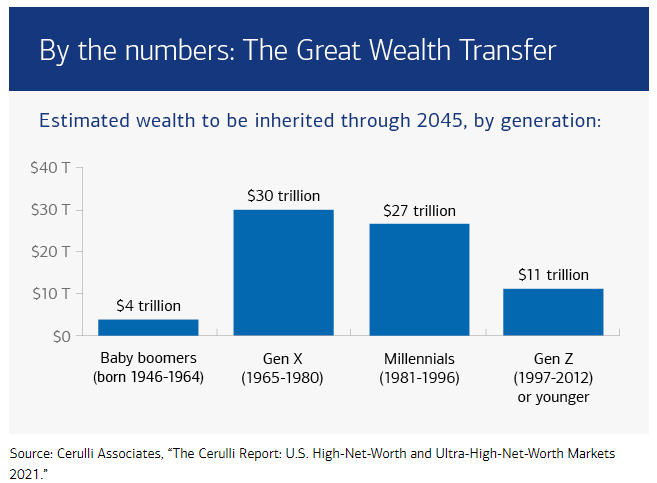

So why care about big-index block flows distorting the markets if it’s just the way things are? Well, one concern is the generational wealth transfer. Boomers are currently sitting on over $30 trillion in wealth, about half of that in Equities, a lot of it accumulated in indexes (directly or through target date funds). If all those folks sell, the above inelasticity could switch from tailwind on returns to headwind. At least that’s the concern.

How does the giant money pile unwind over the next 5-15 years? It’s a giant unknown, but here are a few scenarios, none of which are triggered by the Bank of Japan or short term capital repositioning:

1: Baby Boomers spend down all (or enough to matter) of their equity holdings to live. This seems very unlikely, but since it’s how a lot of financial plans are often made, it seems worth considering. If every old person dies the day they spend down their 401ks and IRAs, it means they have ridden their glidepath out of equity like good little participants. That would switch the retirement market from steady “net index buying” to “net index selling” through those inelasticity multiples, and yes, that would be a headwind. But I don’t actually see this happening. Even if you believe that all of the accumulated stock owned by the Boomers gets sold for cruises, medicine and fast cars, you can make a case that the implied consumption boom would be so good for the economy it would overwhelm the flow effects.

2: Baby Boomers die and leave a bunch of equity to charity. This may be the “worst” scenario. If Trillions of boomer-index-assets gets donated-as-equity to charities, who then sell all that stock to fund operations, it would be bad. If you believed this was the likely path, you would indeed be very wary of the G&K multiple on the way down. $1 trillion to sell over the course of a year? About 10% down in the S&P 500 market cap. ($1T times 5X inelasticity / 40-50T equity market cap.)

3: Baby Boomers die and leave it all to their kids (the thing actually happening).

Here you have to ask yourself: if you inherit your parents’ portfolio, which consists of 70% bonds and maybe 30% indexed equity, are you dumping everything to go buy real estate and fast cars? Or do you hire a financial advisor and reallocate back into a more age-appropriate (higher equity, likely still indexed) allocation? I have no idea, but I can at least create an argument you could get even more equity allocation from the hand-me-down process, not less.

So in short, I’m not that convinced there’s a rundown problem — or that indexing necessarily makes it worse — unless you believe that we’re going to spend down the $31 trillion in retirement accounts. Not impossible, but at least in my crystal ball, you have to really imagine sustained demographic and labor market problems (so lots less goes into the market), and believe a huge chunk of that equity is outright sold, rather than transferred on death.

It’s possible, and by all means, considering the impacts of sustained drawdowns or even just the removal of a few-percent of tailwind is a legit financial planning discussion. One which, hopefully, leads to pretty obvious and rational decision making around diversification.

But this is not an “event.” There is no way to “time” this. Staying out of the market because market structure has warts is a recipe for poverty — market structure always has warts.

My Concern? Efficient Fragility

What actually keeps me up at night is not the target-date-fund rollover nightmare scenarios, or the “we broke capitalism” problems (although we have). What keeps me up is that all of this is going on in a market that, since Reg NMS and Citizens United, has largely been driven by speed and regulatory capture. Both of those have led to hyper-efficient systems governing everything from your Robinhood account to how non-traded bonds settle.

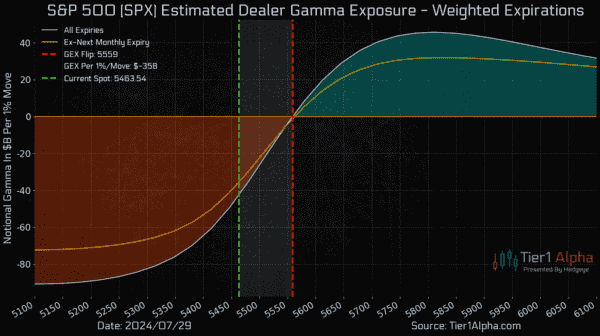

Hyper-efficient, mis-regulated, under-invested systems break. And in a world increasingly reliant on a few ecosystems — say, the S&P 500 ecosystem, from the VIX to SPY to every invisible swap-contract in between — to handle enormous volumes of flow, things can get weird, quickly. The vol guys know this. Dealer positioning is probably now more predictive of stock prices than earnings beats.

But these are already-understood impacts. I worry about the pieces of the plumbing I can’t see easily: how risk moves through the OTC derivatives market and across desks inside big banks, the real-world impacts of one big counterparty screwing up, connectivity and lag issues, custody, settlement and capital adequacy. All the boring stuff.

Indexes aren’t just a way of investing — they’re the entire backbone of market making at this point. If you banned all indexes tomorrow, market makers, institutional investors and traders would just block-trade their own “baskets” anyway. So rather than pretend they are either perfect and have no impact, or that they are evil and should banned, I’m personally going to choose to live in the real world and stay curious, while learning as much as I can.

The Future belongs to the curious.

Dave, this is a brilliant and comprehensive analysis of the indexed investing world. I give a lot of thought to many of these issues.

In particular, I am convinced that specifically S&P 500 weekly/monthly cash flows in retirement/dollar-cost-averaging plans must mean that membership in the S&P 500, regardless of a securities weight creates a premium for that stock over similar stocks. Therefore, as S&P 500 index investing continues to gain market share, this premium would only grow.

Malkiel's point of wanting to own the entire market because all stocks in a market are structurally equal and prices move randomly was an argument I believed in throughout most of my investment career. I was an investor in Vanguard Total Market since 1989 and an investor in VTI since its inception.

I observed and wrote papers between 1980 - 2020 based on this presence. As one who has been involved in the chase for systematic "alpha-plus factors" throughout this span that I eventually surrendered, proving that some market factor led to above-average returns over some past period, only proves that it appeared in the time period measured.

Stock prices are determined by cash flows. Supply and demand. Period. If 30% of cash flows are directed proportionately into S&P 500 stocks, that represents a 0% allocation in that 30% to small cap stocks and stocks with other distinct "smart beta" characteristics that are not in the S&P 500. Therefore, to cancel this effect, the remainder of investors would need to allocate more their flows at a ratio of 1.4 to non-S&P stocks to 1 in order to counteract the S&P 500 effect. However, since most professional active managers are measured against the S&P 500 or a similar index, only those with small cap or other mandates could afford to "bet against" the structure of the market as their tracking errors as measured by consultants would be through the roof.

In other words, Dave, your concerns and focus on flows are right on time. Thanks again

Dave, thanks for writing the article.

There's one thing I don't understand: what's the difference between the scenario where the boomers spend down their assets for their own consumption vs donating their assets to charities who then spend them down for consumption (eg malaria nets)?

You describe one as the text book case and the other as the 'worst case'?

I don't understand. I can see that buying yachts and booking cruises would benefit different industries than manufacturing malaria nets, but at the high level of abstraction we are treating things here, what difference does it make?

Btw, you also didn't mention that, if indexing leads to any weirdness in prices, there are arbitrage opportunities available for the remaining active investors. The fewer active traders remain, the more opportunities per active trader.

For example, if there's a a premium that comes from S&P500 inclusion, you can write a perpetual total return swap on the S&P500 (an instrument that mimics the flow of dividends (and buybacks) coming out of the S&P500) and use the proceeds to buy non-S&P500 assets. If there's a premium, this trade should have positive expected value. You can use some of the proceeds to buy some insurance to smooth out your returns.

Fortunately, index funds are some of the world's most eager stock lenders (one of the few ways they have to boost returns), so that makes the jobs of short sellers to correct premiums easier.